-

Car Reviews

- All reviews

- Midsize SUVs

- Small cars

- Utes

- Small SUVs

- Large SUVs

- Large cars

- Sports SUVs

- Sports cars

- Vans

Latest reviews

- Car News

-

Car Comparisons

Latest comparisons

- Chasing Deals

Electric vehicles have multiple advantages over their combustion powered counterparts, but the nuisance of cabled charging still remains an issue. So can we charge an EV wirelessly like we do with mobile phones?

Electric vehicle ownership in Australia has exploded. In 2011, we bought just 49 electric vehicles. It was early-days for EV ownership in Australia, with the then-obscure Nissan Leaf and now-disappeared Mitsubishi i-MIEV providing two local options.

By 2015, that miserly 49 figure had risen to 759, and by 2020 was up at 5,292 sales – not including Tesla, which does not disclose its Australian sales but may account for as many vehicles again, if not more.

No doubt that EVs are going to be a more common sight on the roads. And with multiple manufacturers announcing ‘phase-out’ schemes for combustion-powered vehicles, it’s only a matter of time before EVs aren’t just a left-of-field option at your local dealership, but rather the only one.

Electric vehicles feature many advantages over their combustion-powered counterparts. They’re generally quieter, faster, easier to service and diagnose, more energy efficient (even when charged with ‘dirty’ electricity), offer greater proportional levels of interior space, and make it easier for engineers to make the car safer in a crash.

New car prices of EVs are also expected to reach price parity with combustion-powered vehicles by 2026 (according to Bloomberg), so that’s an issue that will soon go away.

But despite all of this, there are a few issues holding people back from making the leap to EVs. One of which revolves around charging.

While high-voltage EVs (375V Tesla Model S, 800V Porsche Taycan) and high capacity charge stations offer dramatically lower charge times, many regular EV owners still find the frequent pit stops an irritating issue – particularly as not everyone can afford a six-figure EV that can gulp down hundreds of kilometres of range every few minutes.

Most EVs don’t offer outrageously fast charging, though – and the highest-speed public chargers are also usually pretty expensive. Most electric car owners choose to charge overnight in their own garage or driveway using a wallbox and a wired charge cable – but this still means you have to remember to plug the car in if you’d like to top up the driving range.

Wireless charging (or inductive charging) works around this inconvenience by allowing users to charge their batteries, well… wirelessly.

It’s a potentially ideal solution: you roll into your driveway and position the vehicle over a charging pad. You get out, lock the vehicle and wireless charging commences without messing about with cumbersome charging cables.

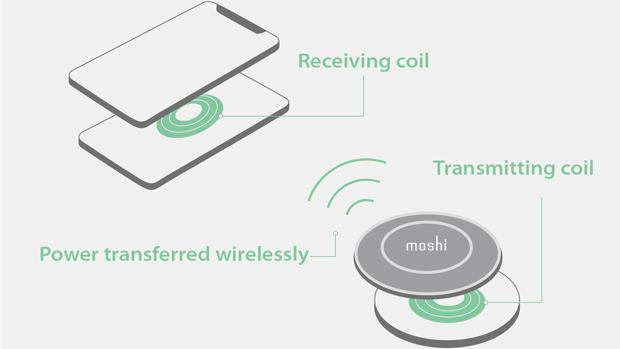

Like wireless charging for mobiles, the philosophy behind wireless EV charging remains the same. You have a battery, a power supply, and a connector that bridges the two systems so that energy can pass between.

It’s no different than how cabled charging works, only that with induction charging the power cable is replaced by a transmitter coil on the power supply and a receiver coil on the EV.

These coils do most of the heavy lifting, utilising magnetic induction to wirelessly transfer the energy across a gap before its partner on the other end receives it. It’s very similar to how radios receive news broadcasts. And, like a radio transmitter and receiver, both must be tuned to the same frequency in order to transfer energy.

It’s this technology that allows mobile phones, laptops, etc to be charged wirelessly – either through a contact pad or with a true ‘wireless’ broadcaster (like the one BMW offered as an optional extra on the 2018 BMW 530e).

It’s a nifty solution to an arguably lazy problem. But while it has helped us on numerous occasions with our phones, it doesn’t mean wireless charging is totally without fault.

While inductive charging has found huge success in the consumer electronics industry, adapting the technology to work in EVs isn’t as simple as scaling the product up and boosting power to eleven.

The first and foremost issue against wireless EV charging is the lingering annoyance of exacerbated charge times.

While inductive charging offers ‘hands-free’ convenience and simplicity, the process of converting electricity to electromagnetic energy (and then back to electricity) acts as a significant bottleneck for high-capacity charging and stretches charge times out even further.

When looking at BMW’s inductive charge pad (called GroundPad) for the G30 530e, we can see how this bottleneck affects charge times.

There are a lot of comparable products and scaled-up hypotheticals we could use in this comparison, but as BMW’s inductive charge pad (or GroundPad) for the G30 530e is one of the few wireless charges that’ve been released by a vehicle manufacturer, we’ll be using it as an example.

BMW says that charging the 9.2kWh battery in the BMW 530e with a standard 2.3kW household electrical outlet will take around “five hours”.

When replaced with BMW’s optional 3.7kW wall-mounted charger, this original five hour charge time drops to “less than three hours”. Initial calculations peg this at around 2hrs 40min, but we’ll add some leeway and increase that to 2hrs 45min.

At 3.2kW, BMW’s ChargePad offers better charging capability than the standard power socket (2.3kW), but a little less than the optional wall box (3.7kW). This means that charge times sit around three and a half hours.

This three and a half hour charge time probably doesn’t seem like an issue when we only look at the BMW’s (small) 9.2kWh battery, but when we compare it with an entry-level battery from a pure EV, say a 38.3kWh Hyundai Ioniq Electric, that original wireless charge time would scale up to 13 hours and 3 minutes. And that isn’t even topping up a ‘big’ battery.

Comparatively, the Ioniq Electric’s maximum charge power (100kW, as supplied by a wired connection) would take just 54 minutes, according to official Hyundai specs.

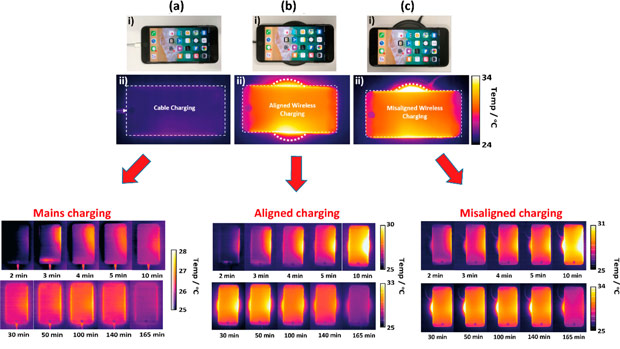

The second mark against inductive charging is the lingering potential for battery degradation and reduced lifespan.

Mobile phone battery degradation brought on wireless charging has been a hotly debated (and sometimes controversial) topic within the consumer electronics industry, with both the New York Times and Warwick University shining light on how mobile phone battery life could be damaged by excessive heat via poor wireless charging practices.

Battery longevity is a significant concern for EV buyers, with many consumers nervously wondering how long their EV has until the brand-new battery completely exhausts itself – and how much it’ll be for a replacement. Will the battery last for five years, eight years, ten years? Will wireless charging reduce that figure – and if so, by how much? And how much is a new battery pack going to cost?

Manufacturers aren’t exactly keen on sharing battery pack replacement prices, so we can’t give you concrete information there. But with industry battery pack prices currently sitting around $137/kWh, as reported by Bloomberg, a new set of Energizer bunnies can’t exactly be cheap ($5247 for new 38.7kWh Hyundai Ioniq Electric battery, estimated).

While we aren’t going to claim that EV batteries will (or won’t) be damaged in the same capacity as a poorly managed mobile phone battery – there’s no long-term data from either side of the argument – we do have to recognise the similarity between the two battery types and that shared vulnerabilities might be likely.

The third swing against induction charging is the paradoxical issue of excessive energy consumption and poor thermal efficiency.

As recorded by a 2016 Middlesex University study, wireless charging uses more electricity than wired-based charging under similar conditions.

During this study, researchers found that charging a Samsung Galaxy S6 Edge mobile phone from one per cent charge to 100 per cent on a wired connection took an average of 85 minutes and drew 0.014kWh from the wall.

When using a wireless charger in the exact same test, outlet power draw increased by 28.5 per cent. Not only did wireless charging consume more electricity, but charge times multiplied as well, with the original charge time increasing from 85 minutes to 201 minutes – a jump of more than 136.4 per cent!

This spike has been seen in other experiments too, with Debugger.medium reporting a 47 per cent leap in wireless power consumption over standard wired-based charging during its own examination of full-cycle charges.

What this data means is that if you were to fully charge a 100kWh Tesla Model S at 23.29c/kWh once a week, every week (52), for a whole year, the price difference between using a cable charger ($1211.08) and an inductive charger ($1,768.17) would total up to a not-so efficient $557.

If we keep our eye on the electricity wasted alone, this disparity (5,200kWh vs 7,644kWh) would add up to a whopping 2,444kWh! That’s enough power to run an Xbox Series X for 12,220 hours or power a four person home for 113 days.

And that’s just one car over one year.

Imagine the amount of power wasted by an entire fleet or suburb’s worth of cars (or state’s worth!) and then multiply that by the average age of the Australian vehicle (that’s 10.6 years). We’ll let you do the math.

Still not convinced? If we run those 2,444 wasted kilowatt-hours past the Hyundai Kona Electric’s average energy consumption (14.2kWh/100km, as tested in our EV Megatest) that would round out to 172km of free driving.

For comparison, Tritium’s ultra-rapid 350kW charger (PK350) has an efficiency rating at 98.5 per cent. And that’s while operating at 350kW/920V and 500A – about 10,837 per cent more than what a wireless charger can put out.

It’s difficult to say at this point in time considering how quickly technology tends to progress.

Currently, wireless charging systems are expensive to buy, costly to run, have the potential to damage an EV’s battery, and aren’t the most efficient way to top up any electrical device.

But cabled charging isn’t a total win-win either – they’re heavy and cumbersome (due to the amount of insulation around them), are often left in an unhygienic state at public charging stations, can be a trip hazard at home, and have the potential to inflict serious electrical injury.

Not to say that electrical cables or charging stations aren’t safe – they are – it’s just that the human body can only handle about .025A (amperes) of electricity before things spiral out of control.

According to the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration, death starts to occur at exposure to 0.05A, with aggressive muscle reactions and nerve damage common injuries likely; 1A stops the rhythmic tune of heartbeats, and 10A brings cardiac arrest, severe electrical burns, and death.

No doubt 10A is a pretty poor level of resilience compared to how much an EV charging station puts out, which, if rated at 350kW/800V (like many fast-chargers are), would make quick work of your hands, arms and torso with its titanic 437A.

And yes, while inductive charging systems are also more expensive and complex than regular power cords, getting a moderately-powered DC charger installed at home isn’t exactly cheap either, with basic 22kW three-phase DC systems starting at around $1,250-$2,500. And that doesn’t include a professional install.

Thankfully, technology is always moving forward, and wireless charging has been targeted by many bright-eyed innovators and start-up companies as one of the most bountiful (and overlooked) areas of the global EV boom.

There’s Aira in the US working on its ‘FreePower’ charger, a free-position wireless charger that doesn’t require manual alignment by the user; Stanford University has theorised an induction charger that adjusts its frequency to maintain 92 per cent efficiency across its range of 61cm; and a peer-reviewed report that demonstrated how wireless charging could be used at ‘room scale’ with an energy efficiency rating of 37.1 per cent.

Then, of course, there’s Qualcomm and its 100 metre long wireless charging road, though no news has come of that since the proof of concept was demonstrated to the public in 2017 (likely due to how much it’d cost).

But a working concept is a working concept – and given that McKinsey & Company recently predicted the EV charging industry will consume an estimated $67 billion of additional investment by 2030 (in order to keep up with the anticipated demands of 40 million new chargers for China, Europe, and the United States), wireless charging could be where the next big breakthrough occurs.

Latest guides

About Chasing cars

Chasing Cars reviews are 100% independent.

Because we are powered by Budget Direct Insurance, we don’t receive advertising or sales revenue from car manufacturers.

We’re truly independent – giving you Australia’s best car reviews.